See part 1 of this series, “All Things Vile and Vicious, part 1: finding God’s glory in the horrors of nature,” here.

In part 1 of this topic, we discussed the importance of allowing children to contemplate animals of all kinds, not just the fuzzy, cute, majestic and familiar ones, but also the unsightly and violent ones. We explored the idea of God as the proto-artist.

I argued that our belief that God is Creator of all, and that what he made is all good, demands that we come to terms with the “horrors” of the created world, and not attribute them to the devil or the disobedience of humanity. If God claims credit for his creation, then we must understand him in a way that makes room for his surprising and even shocking works of creation.

Let’s now turn our discussion to some animal behaviors that are often ignored or moved past too quickly due to their unnerving or stomach-turning features. In doing so we hope to 1) invite new contemplation on God’s works, 2) bring our readers into the company of the scientists who have studied these things in depth, and 3) expand and inform Christian worldview matters.

Fecundity: nature “as careless as it is bountiful?”

If you are not familiar with the word fecundity, it means the rate at which a creature produces offspring, especially those creatures who bear vast numbers of young. You’ve probably heard about species that have hundreds or even thousands of offspring every mating season.

The Disney film Finding Nemo features an opening scene with the mother clown fish having just laid a great mound of eggs. She cherishes them all like a human mother, only to have all but one eaten by a barracuda. In the movie, with cues to the audience about how we are supposed to feel (music, camera angle, etc.) it is a shocking act of violence, and a surprising way to open a Disney film. Of course, in real life this type of event happens every day among thousands of species, unobserved by human eyes, unmourned, and without drama.

Rabbits have a great reputation for fecundity. Rabbits are mature enough to reproduce after only 4 months, and can be ready to mate again immediately after giving birth. Their litter can be from 4 to 12 babies or “kits,” and they can bear such kits many times over the course of their lives.

Because of their rapid reproduction rate, mice can grow in population from 6 to 60 (ten-fold!) in just three months. This may be of interest if you have mouse problems in your home or farm. The typical female produces 5 to 10 litters each year with 5-6 babies each, and the young can begin to reproduce at 30 days. It is perhaps fortunate for us that mice have a high mortality rate.

Seahorses are quite interesting. They are famously monogamous, and it is the males that bear offspring. They can bear from 150 to 2,000 babies in a single season. The birth process of the seahorse resembles something like a confetti canon. You can find videos at the National Geographic website (https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/04/animals-with-most-offspring-fish-eggs-reproduction/)

Bluefin tuna can produce 10 million eggs per year.

The African driver ant is reported by some sources to be the most fecund species producing 3 to 4 million eggs every 25 days – that’s the population of Los Angeles every month.

Excerpt from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Annie Dillard calls fecundity “appalling.” Her comments are so visceral that I will quote her at length. Fecundity, she says, is “teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful…

“A lone aphid…breeding for one year, would produce so many living aphids that, although they are only a tenth of an inch long, together they would extend into space 2500 light years [cited from naturalist Edwin Way Teale]…Lacewings eat enormous numbers of aphids, the adults mate in a fluttering flush of instinct, lays eggs, and die by the millions in the first cold snap of fall.

“A lone aphid…breeding for one year, would produce so many living aphids that, although they are only a tenth of an inch long, together they would extend into space 2500 light years [cited from naturalist Edwin Way Teale]…Lacewings eat enormous numbers of aphids, the adults mate in a fluttering flush of instinct, lays eggs, and die by the millions in the first cold snap of fall.

“The pressure of growth among animals is a kind of terrible hunger. These billions must eat in order to fuel their surge to sexual maturity so that they may pump out more billions of eggs…I feel like Ezra: ‘And when I heard this thing, I rent my garment and my mantle, and I plucked off the hair of my head and of my beard, and sat down astonied. [Ezra 9:3]”

“What kind of world are we living in? Why not make fewer eggs or larvae and give them a decent chance? Are we dealing in life or in death?”

“If an aphid lays a million eggs, several might survive. Now, my right hand, in all its human cunning, could not make one aphid in a thousand years. But these aphid eggs—which run less than a dime a dozen, which run absolutely free—can make aphids as effortlessly as the sea makes waves. Wonderful things, wasted. It’s a wretched system.”[1]

One hesitates to try to explain the “wretched system” Dillard describes in such detail, which allows millions of living species to be destroyed without a moment’s notice. We we come back to this point in part 3 of this article, but for now let us move on to predation, another unsettling aspect of God’s creation.

Let a student focus closely on the natural world for a while, and let her reconcile fecundity with her ideas about God she may have absorbed from kitsch Christian culture, and she might just be forced to grow, to wrestle, to unlearn. She might have to abandon false ideas in order to reconcile the real world with what Christian Smith calls the common belief system among American youth, “moral therapeutic deism.”[2]

Predation: making sense of Nature’s violence

Predation is the killing of one organism by another organism, usually (but not always) for food. We often visualize predation as a tiger pouncing on an antelope in the African savannah, but predation can be observed all around us, not only in dramatic film scenes.

Consider some alternative predation scenarios (which children happen to find fascinating.) Kids look on in amazement and horror when ants gather in armies to overwhelm and consume much larger prey such as caterpillars, reptiles, and birds. Snakes, spiders, ants, frogs, and numerous other species inject their prey with venom to subdue them.

All of these creatures are outfitted with finely tuned, precision body parts that are amazingly efficient at subduing and killing prey. One could justly conclude that they were designed that way.

What about Vultures? They are carnivorous, but they do not kill their own prey. Plutarch related that this behavior seems so unnatural that vultures were considered by some ancients to come from some realm other than earth.

Anyone who has owned a cat has observed that sometimes they seem to kill birds and mice for sport, for the delight of it, with no apparent intention of eating them. Such behavior seems to support the widespread belief that cats are actually sociopaths, killing for pleasure rather than in a desperate impulse to stay alive.

Whale’s mouths have a feature called baleen with which they filter thousands of krill, zooplankton, and small fish in a single swallow. Other types of whales lunge at schools of fish swallowing hundreds at a time. These lunge-feeder whales, called rorquals, have the amazing ability to expand the size of their jaws to encompass a volume larger than their own body. They use this enormous fishing net to scoop up entire schools of smaller fish.

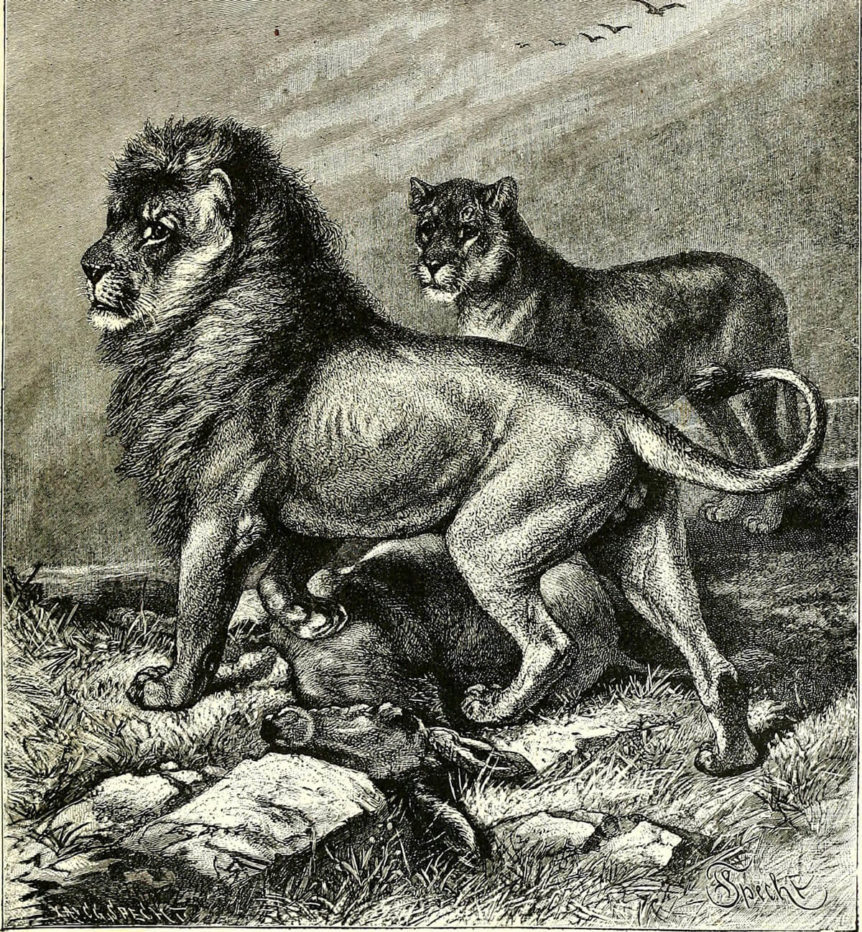

Predation is common and accepted, though it is the subject of great contemplation. Every child knows that tiny creatures are fed upon by larger creatures, which are in turn fed upon by larger creatures, on and on, by increasingly larger animals in a long chain of predation. “The circle of life” —the lion eats the antelope, but the lion dies, its body decomposes into the dirt, and becomes the grass that the antelopes eat.

Some segments of Christianity try to avoid the difficulty by maintaining there was no death prior to the fall. Animals before the sin of Adam were vegetarian, this view maintains. Predation, they would say, is a result of the fall.

This view may be popular and tempting, and some scriptures (mistakenly applied) appear to support it. This view simply does not hold up, as we will explore in part 3 of this series. For now, let us turn to parasitism.

Parasitism: the stuff of nightmares

Parasitism may be considered a subset of predation. Parasites have been defined by E. O. Wilson as “predators that eat their prey in units of less than one.” The parasite is different from a normal predator in that it has an interest in preserving the life of the host, at least long enough to survive and reproduce.

We all know about parasites, so one example will do. Perhaps the most morbid parasite, as bad as any horror movie, are the glyptapanteles, wasp varieties that inject their eggs into the bodies of living caterpillars. The caterpillar goes on about its business as if it doesn’t know what’s going on. But inside it, the wasp larvae grow, molting and shedding their exoskeletons. As the larvae grow, the caterpillar’s body swells up. When the larvae are mature, they all emerge together bursting out of the body of the caterpillar in the space of an hour.

But they are not done with him yet. In the final phase, the wasp larvae gestate in a web of cocoons outside the body. Not only does the poor caterpillar become the incubator for the wasp larvae like some alien body-snatcher scenario, but after the emergence of the larvae, it becomes a sort of zombie slave, held under larvae mind-control, so that it protects the larvae as they continue to mature. Eventually the caterpillar dies of startva and the baby wasps emerge from their cocoons and fly away.

But they are not done with him yet. In the final phase, the wasp larvae gestate in a web of cocoons outside the body. Not only does the poor caterpillar become the incubator for the wasp larvae like some alien body-snatcher scenario, but after the emergence of the larvae, it becomes a sort of zombie slave, held under larvae mind-control, so that it protects the larvae as they continue to mature. Eventually the caterpillar dies of startva and the baby wasps emerge from their cocoons and fly away.

It is hard to know what to do with such animal behaviors that are the stuff of nightmares.

Is creation really suitable for children?

As we reflect on these bizarre and unnerving facets of nature, we face our original question: is creation suitable for children? Would you shrink from telling your students about the glyptapantele wasp?

And perhaps this is a major part of the issue—things that strike us as dark and horrible may simply be because our particular western, 21st century, Disneyfied sensibilities form an interpretive grid that makes us squeamish.

But perhaps the Creator Artist who made the world doesn’t see it the way we do. Perhaps in God’s creation economy, in ways that are higher than our ways, all the shocking behaviors we see in animals are “very good.” If this is true, then who are we to say otherwise?

Let a student focus closely on the natural world for a while, and let her reconcile fecundity, predation, and parasitism with her ideas about God she may have absorbed from kitsch Christian culture. She might just be forced to grow, to wrestle, to unlearn. She might have to abandon false ideas in order to reconcile what has been carefully selected as appropriate for her with the real world.

We will explore various Christian responses to the “horrors of Nature” in part 3 of this series. But while we wait for this final part, let us consider C.S. Lewis’s wise words in The Chronicles of Narnia that Aslan “is not a tame lion.”

[1] Dillard, Annie. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Harper Perennial, 2016.