by Jeffrey Allen Mays

Why this subject matters

Much of the debate over the age of the earth takes place in geological terms. Scores of books have been published on the subject, each side holding forth with points about radiometric dating, volcanic activity, fossils, and rock formations. My field is not geology. I am a theologian by training, and Biblical interpretation has been a particular area of study.

For this reason, I am writing this article from the standpoint of Scripture. I hope to show my readers how the Bible invites a non-literal interpretation of Genesis 1-2. It does not demand the strictly literal one that has compelled Youth Earth Creationists to the difficult position of standing against a world of other Christians, not to mention the non-Christian world that considers the subject long closed.

To me, it seems that this is the appropriate grounds on which to have this debate. The geological questions would suddenly disappear if the Young Earth faithful could see, with careful study and fresh eyes, that the opening chapters of Genesis do not call for literalist reading. And while clear biblical interpretation might free a Christian conscience regarding the Old Earth view, I strongly doubt that arguments from science will never overturn a mind convinced that faithfulness to God is at stake.

It is very important to Christian theology that the teachings of the Bible and the things we observe in the world be in harmony. Christians believe that both the Bible and the created world come from the same God. If the findings of science disagree with what we think the Bible is saying, we clearly have more work to do. There is a logical contradiction if God’s Word and God’s Works appear to disagree.

The impetus to reconcile scripture and science has another source: the testimony of the church before a watching world. Sadly, the belligerent and uncompromising stance of the Young Earth movement and the overwhelming, multi-disciplinary evidence for an Old Earth has made the Christian faith a non-starter for many people. It is tragic that a matter of secondary importance has risen to such prominence and barred the way into the kingdom for many who see Christians as those who “check their brains at the door.” A church that presents a plausible, reasonable, unified message removes roadblocks to the gospel.

To those who grew up in a Young Earth church and family, the Old Earth view may appear baffling. After all, what could be clearer, they say, than that the days of creation are six ordinary 24-hour days? And it is very understandable that, without an explanation of why many Christians take the OEC view, it would appear that they are compromised at heart, loving the approval of man over the truth of God, simply finding a clever way to elude the plain words in Genesis 1 to curry favor with the world. But Young Earth Creationists (YEC) should understand that Old Earth believers are not averse to challenging doctrines; we believe other more intellectually challenging ideas: the miracles of the Christ, the resurrection, the virgin birth, the trinity. The age of the earth is not an issue that challenges the will or the submission of the mind to the Word of God; it is mundane, unspiritual, non-redemptive, and a predominantly modern question.

Literalism

There is one critical assumption upon which the YEC view rests, that is, as I have mentioned, the assumption that Genesis 1 must be interpreted literally. In this view, Genesis 1 functions as a documentary, like a journalist’s eyewitness report, of the events of creation. YEC defenders like to say that since only God was present at creation, only he knows the details of creation, and he recorded them for us in Genesis 1, literally. To many, this sounds like an open-and-shut case. But why should Genesis 1 be the place to insist upon literal interpretation? The rubric of literalism is not applied by YEC believers everywhere in scripture. Consider the case of Jesus’ command to cut off a hand or gouge out an eye if it causes us to sin (Matt. 5:29). But there is an even greater problem.

With literalism, we are immediately on unsteady ground. When we ask what the word “literal” actually means, we find that it is virtually meaningless in biblical study because the unanswerable question immediately follows, literal according to whom? To 21st century American evangelicals? To 8-year-old children? To 16th century theologians? To Moses and the children of Israel? The word literal is a completely subjective term. In the YEC explanation, literal means the plain and simple or “face-value” meaning of the text. But what seems a “face value” meaning in one time, language, and culture may be quite different in another. Face-value is simply another way of saying the way it seems most natural to me. Most sadly, this stance places the modern reader’s ego in the center. It lacks humility and self-suspicion that we must bring to the study of scripture.

Assuming a literalistic view completely avoids the question, Did the author mean it to be taken that way? We do not insist upon literalism when we read about “wisdom calling out in the streets” (Prov 8), or “Lebanon leaping like a calf” (Ps. 29:6), or Jesus’ statement that we should cut off hands and gouge out eyes that sin (Matt 5:30). These passages contain meanings that are theological, moral or spiritual, but decidedly not to be taken merely at face value.

Clues to a non-literal reading

So where do we start in discerning how a particular passage should be read?

A great place to start is to consider the genre of the passage, or what kind of literature it is. The genre of a piece of writing creates expectations in the reader about how a passage is to be read. Genre is identified by clues in the text itself. Try this little exercise on identifying genre:

- “Roses are Red” – you know this is a poem, you expect it to have 4 lines, and you already know the second line

- “Dear John” – you know that this is a letter, not just any letter, but a breakup letter from a girl to her sweetheart, that gained popularity during World War II

- “Once upon a time…” – you know that this is a story, probably a fable

- “The Spanish Flu was a deadly pandemic that lasted from 1918 to…” – this one may be more difficult: a research paper? A page from a history textbook? We know for sure some genres that it is not – a poem, a current news story, a recipe for banana bread

What is the genre of Genesis 1-2? Most scholars agree that this passage falls into the genre of the Creation Narrative. There were many creation narratives in the ancient world; the Egyptians had one, the Sumerians, and other cultures. Creation narratives commonly contain deities performing acts to create mankind and the heavenly bodies. They contain highly symbolic features. They are not, however, the same type of literature as, say, the book of 1 Samuel or Esther or any fairly obvious historical narrative. Creation narratives are a unique and identifiable genre, well-known to cultures surrounding ancient Israel.

Verb tense. Despite the points about genre above, YEC interpreters usually claim that the genre of Genesis 1 is historical narrative. They base this largely on Hebrew verb tense used in most of the chapter, called the wayyiqtol. In books of the Bible where a sequence of events is happening, the wayyiqtol is normally used. For example, “And Joseph dreamed a dream, and he told it to his brothers, and they hated him all the more.” It is sometimes called the narrative tense. However, it does not necessitate actual events. For example, in 2 Samuel 12, when Nathan the Prophet tells King David the parable about the rich man who took the poor man’s only sheep to feed a guest, the author uses the wayyiqtol. So the presence of this tense in Genesis 1-2 only means a story is being told with no indication one way or the other about whether it is a documentation of literal historical events.

It is true that there is a story-telling going on so that the narrative tense is to be expected, but there are other prominent literary features that give us a clue about how to read the passage. Many literary devices and poetical elevation that signal to the reader a genre that is much more nuanced than a simple historical narrative, and should be read as something much more than a simple catalog of events.

Repetition. Repetition is a common element of Hebrew verse. For example,

For three transgressions of Damascus and for four, I will not revoke the punishment…

For three transgressions of Gaza and for four, I will not revoke the punishment…

For three transgressions of Tyre and for four, I will not revoke the punishment…

[and so on for Edom, Ammon, Moab, Judah and Israel] Amos 2

and also,

A time to be born, and a time to die,

A time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted,

A time to kill and a time to heal, etc Ecclesiastes 3

In addition to being an aid to memorization, repetition is evidence of artistry, similar to the way repetition in songs works. Repetition shows that the author is speaking in an elevated mode for some literary purpose such as a parable, song lyrics, or prophecy. The author Moses knew it was appropriate when writing a creation narrative to appeal to the Hebrew aesthetic sense.

YEC defenders often mischaracterize the OEC view by saying we claim Genesis 1 is “just a poem.” But it is much more nuanced than that. Genesis 1 is charged through with heightened quality and liturgical value. Repetition was immediately recognized by the ancient Hebrews as a special voice and elevated mode of speech. Repetition is seen in the phrasing,

And God said, “Let there be…”

And God said, “Let there be…”

and

And it was evening and it was morning, the third day…

And it was evening and it was morning, the fourth day…

And it was evening and it was morning, the fifth day…

and also,

And God saw that it was good…

And God saw that it was good…

This artistic stylizing is not surprising given what this opening chapter is: these sentences are the opening words to the constitution of the redeemed people of God. Why should we expect a flat journalistic account?

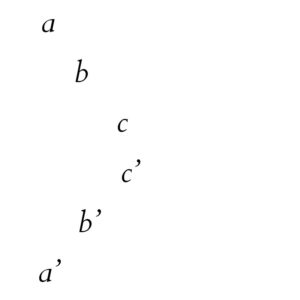

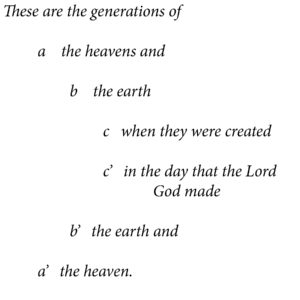

Chiasm. Another evidence of artistry is the use of the favorite Hebrew literary linking device called a chiasm, named after the Greek letter χ (chi). A chiasm is a sequence of phrases that has a thematic structure that looks like the following or some close variation:

The first series of phrases (a, b, c) are repeated in reverse order (c’, b’, a’). Genesis 2:4, a key turning point in our passage, contains a very nice chiasm.

More could be said about the appearance of chiasms in Genesis, but the point here is that more artistry, cleverness, and style are being used by the author that transcends the simple relation of a sequence of events.

Broad strokes. Topically, Genesis 1:1-2:3 deals with the grandest categories: light and dark, day and night, land, sea and sky, plants, animals and humans. Notice there are no specifics, only broad generalizations. But immediately after the chiasm in Gen. 2:4, the scope changes radically, zooming in to specific details: minerals (gold, bdellium, and onyx), plants (bush of the field, ‘small plant’, tree of life), place names (Eden in the east, rivers Gihon, Pishon, Tigris, Euphrates). We have transitioned from what reads like a hymn in 1:1-2:3 to a much more detailed account beginning in 2:5. The manner of speech is noticeably different.

Soliloquy. One point that makes Genesis 1 quite different could be called the “staging.” Here, only God acts and only God speaks. He uses the plural “let us” which many take to be an early indication of the trinity, as God takes counsel within himself. This divine monologue is unique in all of scripture. In the rest of the Bible God is always interacting with man or angels, but never alone to himself. In this one place, he is like an actor on a dark stage with a single spotlight on him, speaking unilaterally, calling things into existence by the word of his power. For what it’s worth, it reminds me of an overture of a symphony, or the opening monologue in a Shakespearean play: a short, elevated speech, perhaps to the audience, or simply expressing thoughts into the air, before the regular action of the play begins, a kind of theatrical suspension.

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

or

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

This one-of-a-kind feature suggests that the genre is much more elegant, nuanced, and theologically pregnant than historical narrative allows.

Exalted mode. Similar to the ‘broad strokes,’ we should notice the unusual choice of heightened vocabulary in 1:1-2:3: ‘firmament’ instead of ‘land;’ ‘expanse’ instead of ‘heavens;’ ‘birds of the air’ and ‘fish of the sea,’ ‘creeping things.’ But again, all of this ceases after 2:4. The writer reverts to more ordinary terms of land, sky, and birds. What does this indicate? Though it may not be immediately apparent to western, 21st-century ears, it is what a speaker does when he/she is orating about matters of grand significance. A newspaper reporter doesn’t speak this way or else he risks being misunderstood, but an old school preacher or statesman-politician might. Exalted mode grabs attention and it elevates the listener to a more enraptured state of listening. Again, the point here is that it is evidence of oratorical artistry beyond mere recitation of geological and biological data. That suggests that the author’s intended meaning, the burden of the story, does not reside at the level of scientific details, but at a spiritual and theological level, the level of the essence of the cosmos and human beings, and of God’s sovereignty and plan of redemption.

Historical Context. Much could be said here. But in short, we must remember that this account was written by Moses to introduce Yahweh to the oppressed Israelite slaves newly-freed from 400 years of bondage to Egypt. They were dealing with the God of their fathers who was redeeming them. They knew about the Egyptian gods in the sun, moon, rivers, and so on. But this creation story was telling the Hebrews that their redeeming God made, made the sun, moon, and rivers, asserting God’s great supremacy over the Egyptian gods. But for Moses to go straight into relating the scientific particulars of where the earth came from, as if this was the first thing God wanted to say to them, is absurd. That is not a concern of Genesis 1. OEC explanations frequently point out that scientific thinking was not part of ancient concern. The Bible is not a science textbook, but a history of redemption.

Conclusion

In the creation account, we have the telling of a story in an elevated manner using many poetical devices and artistry. These genre clues signal to the listener/reader that we are having a little fun here! This isn’t just a sequence of historical events like the conflict between two armies. There is the idea of joy, even singing or chanting. It’s storytime! and whether or not it literally happened that way is not the point. God is communicating spiritual truths here, not geological or scientific ones. The opening chapters of Genesis are theologically pregnant, they are meant to lead us to the right theological conclusions that we need to understand God, the world, and ourselves from a theological standpoint, not scientific: God as Creator, marriage, man’s co-regency over the animals and the world, setting up a 7-day week with a Sabbath built-in, and so much more. The last thing God (or the Hebrews) was eager to communicate was the particularly modern question of the age of the earth. That’s not a question that anybody was asking.

But couldn’t it be both? Many YEC believers want to ask, Cannot the Creation account be both theologically and scientifically accurate? My answer is, it could be, but it’s not. It doesn’t function that way. Why do we want to force it into modern categories? Does God so regard modern man’s science as to take special measures to entertain our scientific curiosities in inspired scripture? Was that the first thing on his mind when encountering the Israelite slaves? No. On the contrary, this reveals how scientifically over-committed YEC defenders are without realizing it. It is a hermeneutical mistake to bring modern scientific questions to the Bible seeking answers.

I could go on about the use of anthropomorphism (for example, did God really need to rest?), the problems with light existing before the sun was created, the mixed use of the word ‘day’ to mean both a creation day and the period when it was light (the 12-hours of daylight), the significance of the seventh day, the juxtaposition with other creation stories in the ancient world, and numerous other matters.

The point is that Genesis 1 does not demand a young earth interpretation, and this opens the door to the harmonization of scripture and the modern geological timeline. The creation story of the Bible is not trying to give us actual geological times but is using the structure of one week as a story-telling device to convey concepts of theological and redemptive importance.

Anticipated responses

If you allow a non-literal interpretation of Genesis 1, it will open the door to people making the Bible say anything they want. And then anything sinful man doesn’t like in the Bible can just be dismissed as “figurative.”

There are many things wrong with this point.

First, this statement is a fine example of question-begging: it presumes the YEC stance of literalism is true. Who said we should assume that literal is the default? What if a figurative interpretation of any particular passage in the Bible is actually the correct one, as in most prophetic scriptures? The presumption of literal interpretation would necessarily lead to mistaken interpretation. A piece of literature tells us how to read it, not vice versa.

Another way to say this is that literalism is not the guarantor of truth, accuracy, or theological usefulness. I have already mentioned the parables of Jesus, his words about “cutting off your hand” or “gouging out your eye.” Was the prodigal son an actual, living man in 1st century Israel, someone Jesus knew and was telling a factual account about? No, it was just a story with a spiritual application.

But I will still answer the question — it is rather the YEC side that is making the Bible say what they want. By bringing scientific questions to an ancient creation narrative, they are stretching the intended function of Genesis to suit modern appetites and interests.

Finally, the point above is an example of the slippery slope argument which is a logical fallacy. Just because we take a step in one direction does not mean we will inevitably take more steps. And if the one step is a step toward the truth, then the ‘slippery slope’ is an argument that hinders us from moving closer to the truth. It uses fear of unintended consequences in an attempt to scare the audience.

We are not spiritualizing or allegorizing Genesis 1. We are not saying it is ‘merely figurative,’ or ‘mere poetry.’ We are saying that there is textual evidence that the passage communicates its message in an elevated voice and therefore invites interpretative freedom. And serendipitously, this creates a path to the theological imperative of harmonization of scripture with our observations of the physical world.

Why not just hold to what we’ve always believed? Can’t we just go on believing the earth is young and go about our lives?

Many generations of believers have assumed the earth was young, and that view served them well in their time. This is not a creedal issue. Given that the earth is millions of years old, God seems to have been in no hurry to disabuse humanity of that technical mistake by allowing us to go on for thousands of years never imagining the cosmos was that old. That just goes to show again where God’s priorities lie: in redemption of humans and his intention to restore communion with them.

But in today’s world, it is not OK to just go on believing in a young earth any more than it is believing in a flat earth. Holding to YEC views creates many unnecessary problems and conflicts that hinder God’s work in the world. Seeing that Genesis 1-2 does not demand a young earth view is beneficial for several reasons:

- it enables us to be faithful disciples who are willing to lay down idols of the mind if they are found to be mistaken

- we should not be content with the dissonance that comes from believing that God’s Word and God’s Works offer differing testimony

- we imitate Christ in loving the world of the lost, eliminating unnecessary barriers to the gospel

- we show the watching world that Christianity is actually a reasonable faith

- we show the watching world that science is actually our friend is a God-honoring endeavor

The uncompromising nature of the YEC view, made increasingly public in recent years, has made Christianity unnecessarily unpalatable and even ridiculous to non-believers. Like the Pharisees, it sets an unnecessary obstacle before those who would enter the kingdom. Our desire to attract unbelievers to the Christian faith leads us to remove that obstacle. Augustine said as much in the 5th century:

“Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens…and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn…If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven when they think their pages are full of falsehoods…?

I hope that those who have been fearful of adopting the old earth view because of dire warnings that they are turning against God will see that, on the contrary, this is an opportunity to grow in the knowledge of God and the scriptures.